“If the greatest teaching tools delight the heart as they instruct the mind, then Adam Gidwitz has just given us 337 of the most bizarre, funny, and awesomely epic pages for talking to our children about Western Civilization’s history with prejudice and persecution.”

-The Book Mommy

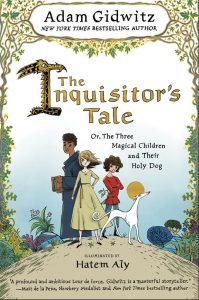

Read more about teaching The Inquisitor’s Tale here.

Click here to download an Educator’s Guide to The Inquisitor’s Tale.

Click here to read School Library Journal‘s “Teaching Ideas and Invitations” for The Inquisitor’s Tale.

Click here to download The Inquisitor’s Tale Annotated Bibliography

Where Did This Story Come From?

My interest in the Middle Ages is entirely my wife’s fault. We met in college. Even back then she knew that she wanted to be a professor of medieval history. Our first trip together was to Northern England, where we went on a week-long scavenger hunt for missing pieces of medieval stained glass. (We found them!) We continued to take trips to Europe to visit museums, monasteries, castles, churches, libraries, dungeons, ancient forests, and medieval garbage dumps. (In fact, my wife spent a whole week excavating one.) We even lived in Europe for a year. My wife spent all day, every day, in libraries, reading medieval books. I spent all day, every day, cooking, eating, and dreaming up this novel.

So how much of this novel is real, and how much is made up? That’s a complicated question.

Many of the characters are real. King Louis, Blanche of Castile, Jean de Joinville, Robert de Sorbonne, Roger Bacon, Gwenforte the Holy Greyhound (yes, there was a Holy Greyhound, though she was a he, and his name was spelled Guinefort).

Some of the events really happened, too. The Holy Nail really was lost (and found). Knights really did sink into the quicksand surrounding Mont-Saint-Michel. And, tragically, some twenty thousand volumes of Talmud really were burned in the center of Paris.

Other events in the book are inspired by legends of the Middle Ages: William’s battle with the ends, the dragon of the deadly farts, Jeanne recognizing the true king.

Below are some notes to help you sort through what is history, what is legend, and what is completely made up in The Inquisitor’s Tale.

JEANNE’s character was very loosely based on Joan of Arc (whose name, in French, is Jeanne). Joan of Arc was a peasant girl, and she, like my character Jeanne, had visions. There is also a legend about her being brought before the King of France and kneeling to one of his courtiers—who turned out to be the real king in disguise. The similarities between Jeanne and Joan of Arc end there, though. Joan lived two hundred years after my story takes place, was a military genius even as a child, led the armies of France against the English, was captured, horribly tortured, and then executed.

My wife and I lived for a time in Rouen, France, right across the street from where some of the worst torture took place. The more I learned about Joan of Arc, the more upset I became. I felt that her fate wouldn’t have been nearly so gruesome or so tragic had she not been both a peasant and a girl. To the lords of the Middle Ages, there was no figure more powerless and more exploitable than a peasant girl. I wanted to depict that in my story—but more gently. After all, not every peasant girl was treated as badly as Joan of Arc.

By most counts, PEASANTS accounted for ninety percent of the European population in the High Middle Ages, when The Inquisitor’s Tale takes place. Just like Jeanne, peasants typically lived in villages near farmland. None of the land they worked or lived on belonged to them, though. It belonged to the “land lord,” who was usually either a noble or a religious institution. Each peasant family was given a plot of land to build a house and raise animals on, as well as a furrow of the fields to grow food for themselves. In exchange, they had to work the lord’s land, the demesne, once a week, and also pay rent or taxes to the lord once a year.

There was a hierarchy of peasants in the Middle Ages. Some were “free peasants,” who didn’t own any land but could, at least, move to another manor if they wanted. Bonded peasants, or serfs, could only leave if their lord gave them permission. Serfdom wasn’t quite slavery (they couldn’t be bought or sold, for instance), but it was close. If you want to learn more about peasant life, or about any of the topics I take on in this book, I recommend a variety of sources in the Annotated Bibliography.